Title: Navy Fireman 1st Class, Civil War; Medal of Honor

Birthdate: November, 1832

Death Date: January 30, 1883

Plot Location: Section 104, Lot 26, northwest quarter

This hero deserves a better marker. There is one, but it was placed in the wrong cemetery, as explained below.

Matthew was from Ireland, sailing the seas to arrive in America when he was 12. Life for his next dozen years is not well documented but perhaps something about the sea life was attractive to him.  In the summer of 1858 he joined the Navy. With the outbreak of the Civil War he re-enlisted and was assigned to the newly-built wooden steamship USS Richmond.

In the summer of 1858 he joined the Navy. With the outbreak of the Civil War he re-enlisted and was assigned to the newly-built wooden steamship USS Richmond.

Like locomotives of that era, steam engines required a lot of coal. The job of shoveling all that coal fell to “firemen” like Matthew.

The Richmond played an important role in blockading the port of New Orleans with the goal of strangling the South’s economy and contributing to an eventual surrender. It was early in 1862 when Matthew’s ship joined the West Gulf Blockading Squadron under the command of Flag Officer David Farragut. His goal was to seize the city. The Richmond was part of that engagement in April and it continued along the Mississippi River to take Baton Rouge.

However, it wasn’t until March of 1863 that significant gains were made further upstream. Farragut’s flotilla came under heavy fire at Port Hudson, 15 miles north of Baton Rouge. It was here that Matthew was forced to play a greater role than that of a coal heaver.

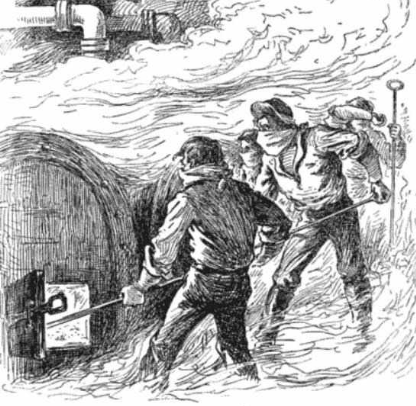

His Medal of Honor citation provides the rest of the story: “Serving on board the U.S.S. Richmond in the attack on Port Hudson, 14 March 1863. Damaged by a 6-inch solid rifle shot which shattered the starboard safety-valve chamber and also damaged the port safety-valve, the fireroom of the Richmond immediately became filled with steam to place it in an extremely critical condition. Acting courageously in this crisis, McClelland persisted in penetrating the steam-filled room in order to haul the hot fires of the furnaces and continued this gallant action until the gravity of the situation had lessened.”

Matthew and three other firemen were awarded the Medal of Honor four months later, on July 10. David Farragut received a promotion that summer to Rear Admiral. It wasn’t until a year later that Vicksburg and Port Hudson surrendered. Control of the Mississippi meant the Confederacy was cut in two.

Matthew and three other firemen were awarded the Medal of Honor four months later, on July 10. David Farragut received a promotion that summer to Rear Admiral. It wasn’t until a year later that Vicksburg and Port Hudson surrendered. Control of the Mississippi meant the Confederacy was cut in two.

Matthew continued as a fireman aboard the Richmond until the other major Gulf port was taken. That was yet another year later, August of 1864, in Mobile, Alabama. Mobile Bay was heavily mined, with what were then called torpedoes. It was here that Admiral Farragut shouted a command to press forward anyway, which became famously shortened to “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!”

The Medal of Honor was awarded to 29 members of the crew of the Richmond after that battle. Besides Matthew, three others are buried here at Mount Moriah and have their own Notable life stories: James Martin, John Smith, and Alexander Truett.

Having completed his term of service in September, Matthew returned to life in Philadelphia. Instead of stoking fires he took a job that required putting them out, as a firefighter. Church bells chimed at Broad Street Methodist Episcopal when he married Elizabeth Baxter in 1867. They had three girls and a boy.

Martha McClelland, Matthew’s mother, was living with them according to the 1880 census. Matthew’s job was listed as “bell ringer” which means he may have been assigned to drive the fire wagon. His mother died January 2, 1883 and Matthew died of heart problems 28 days later. Elizabeth and one daughter both died of tuberculosis before they were 50 and their son died of kidney disease at age 24.

The remains of Matthew and his mother were both placed in a temporary vault at Lafayette Cemetery. Mount Moriah Cemetery records show they were relocated here in February on the Yeadon side in section 104. His wife, son, and one daughter would eventually join him.

In 2006, the Medal of Honor Historical Society of the United States incorrectly assumed that Matthew’s body had been moved from Lafayette Cemetery to Evergreen Memorial Park in suburban Bensalem during a mass reinterment in 1947. Evergreen became Rosedale Cemetery in 1960. Based on that, the MOHHSUS then mistakenly requested that the VA place a bronze grave  marker, shown here, near the mass grave in Rosedale Cemetery. In 2015, volunteers at Mount Moriah located 3 of the four “corner markers” for lot 26 and confirmed in the records that this is where that bronze marker actually belongs. Someday, hopefully, that will happen.

marker, shown here, near the mass grave in Rosedale Cemetery. In 2015, volunteers at Mount Moriah located 3 of the four “corner markers” for lot 26 and confirmed in the records that this is where that bronze marker actually belongs. Someday, hopefully, that will happen.

Support the Friends of Mount Moriah

Help us in our mission to restore and maintain the beautiful Mount Moriah Cemetery by donating to our cause or volunteering at one of our clean-up events.