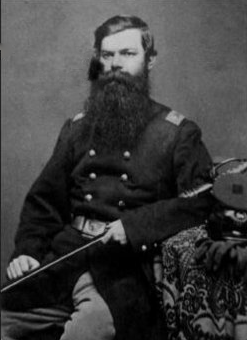

Title: Army Colonel, Civil War

Birthdate: April, 1828

Death Date: April 20, 1883

Plot Location: Section 30, Lot 51

Edwin Ruthwin Biles was born in Philadelphia to Joseph T. and Rebecca C. Biles. His father was a carpenter, and the 1850 census shows he had seven younger siblings.

His early adult years were somewhat undistinguished compared to others who were involved in the extraordinary events of that era, such as the Frontier Wars, the Gold Rush in California, the Oregon Trail, and the movement West to find new settlements. Edwin began employment as a clerk, and he joined the Army as a sergeant in the Mexican War in 1847. Following that he resigned and went back to clerking in Philadelphia until 1861 when he was 33.

Then came a complete turnaround, and he was to become an excellent field officer in the Union Army, participating in many significant battles throughout the War.

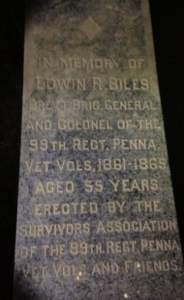

In 1861 he joined a newly formed regiment, the 99th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, as an Adjutant, a non-commissioned officer just above a Sergeant who assists the Commanding Officer. He remained with the 99th until the end of the war but in increasingly higher levels of rank. He was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel on July 1, 1862 and to Colonel on August 23, 1864. Near the end of the war he received the honorary rank of Brevet Brigadier General.

He was wounded three times, at Spotsylvania Courthouse in the Wilderness Campaign on May 12, 1864, at Deep Bottom in the Siege of Petersburg three months later, and at Petersburg on March 25, 1865, 15 days before the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House.

From August 8, 1861 to July 4, 1862 the 99th was stationed around Washington protecting the Capitol. Their first taste of battle was at Bull Run on August 30th where three were killed and ten wounded in three days of fighting. The next major battle was at Fredericksburg which was a disaster for the Union. (For a more detailed description of the battle see the paragraph in the “Notables” story of Colonel William “Buck” McCandless.) Next came the Battle of Chancellorsville in Spotsylvania, Virginia (April 30- May 3, 1863) which was another defeat for the Union. The Union brought 134,000 to the fight, while the South had only 61,000, but in the end the South prevailed due to General Robert E. Lee’s battlefield tactics. Two months later the 99th fought at Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1863) and the Union prevailed, making it the first battle in the East where there was a clear victory.

During the remainder of 1863 and the first four months of 1864, the 99th fought a number of minor battles (Bristoe Campaign, Kelly’s Ford, Mine Run Campaign, Payne’ Farm, and Brandy Station) sparring with Lee’s army in Virginia.

In May, General Ulysses S. Grant took command of the Army of the Potomac and for the first time in the Civil War, Grant and Lee directly opposed each other on the battlefield. What followed until the end of the war in April, 1865 was a series of confrontations that were bloody, exhausting, closely fought, and characterized by large casualty rates. The Union actually lost more men in most of the battles than the South but the percentage of loses sustained by the South as compared to the size of their army was greater. It became a war of attrition.

The Battle of the Wilderness was fought from May 5-7, followed by Spotsylvania and Spotsylvania Court House from May 8-21. Neither side won, and Grant slipped away to the southeast toward Richmond to Cold Harbor, a crossroads named after a tavern (June 1-12). The Union suffered enormous casualties (12,700 vs the South’s 5,300). Grant slipped away again to the South to attack Petersburg on June 16th, and this began the Siege of Petersburg which lasted until April 2, 1865.

The 99th participated in all of the battles, as well as the Siege. While there, the 99th was billeted in Fort Sedgwick, a structure covering over two acres, built of logs, sandbags and dirt. The fort was renamed “Fort Hell” by the men because of its proximity to the enemy (about 100 yards) making it a perfect target for artillery fire and snipers. The regiment made eight attacks on enemy forts during the siege.

Lee was supplied during the war from the South by a rail line that ran from Wilmington, North Carolina to Petersburg. It was under the South’s control until the start of the Siege. Grant wanted to destroy the line by ripping up the tracks, and he sent troops south from Petersburg in June and August. The raids were successful, so Lee had to offload supplies onto wagons for the trip to Petersburg. In December the 99th was in a unit tasked with going further south to Jarratt, Virginia to destroy about 16 miles of track. They achieved their objective, making it no longer possible for Lee to supply Petersburg.

Petersburg fell on April 2, 1865 and Lee led his army west toward Appomattox. Lee surrendered on April 9th. Colonel Biles was mustered out with the 99th Regiment in July of 1865. He returned to civilian life as a clerk in the Philadelphia Recorder’s Office. Edwin married Julia Kelly in 1864 and they had a boy and a girl. After Julia’s death in 1876 he married Sarah Furr three years later to help parent his teenage children. Then he died in 1883 of liver disease.

What kind of field officer was Edwin R. Biles? He moved up in rank from Adjutant to Colonel from 1861 to 1865, leading his troops during the toughest fighting in the War, and he was brevetted a Brigadier General for gallant and meritorious service. Rev. Legh R. Janes, a Chaplin in the 99th during the winter 1864-65 said of him when writing to one of the Chaplin’s relatives, “My Colonel, Edwin R. Biles was an old untamed soldier, and served in the Mexican War as Adjutant General. He was an infidel, with some redeeming traits of character.”

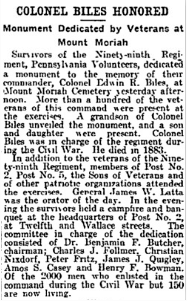

Edwin was originally buried in Glenwood Cemetery in Philadelphia. That cemetery ceased operations and he was re-interred at Mt Moriah on April 27, 1906 beside his second wife, Sarah, who died in 1903. Members of the 99th provided this monument at a ceremony attended by Edwin’s children.

Edwin was originally buried in Glenwood Cemetery in Philadelphia. That cemetery ceased operations and he was re-interred at Mt Moriah on April 27, 1906 beside his second wife, Sarah, who died in 1903. Members of the 99th provided this monument at a ceremony attended by Edwin’s children.

Support the Friends of Mount Moriah

Help us in our mission to restore and maintain the beautiful Mount Moriah Cemetery by donating to our cause or volunteering at one of our clean-up events.