Title: Watchmaker

Birthdate: March 27, 1813

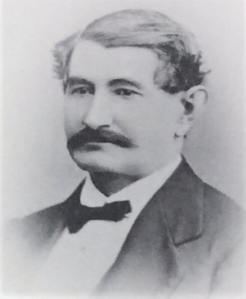

Death Date: June 15, 1892

Plot Location: Section 43, Lot 50, northeast quarter

William’s family came from England and settled on the Maryland coast south of Delaware. As a teenager he came to Philadelphia to learn the craft of watchmaking. Completing his apprenticeship at age 21, he was hired to repair watches for a jeweler in Alexandria, Virginia.

He apparently liked his new position. Three months later he traveled to Philadelphia to marry Eliza Jones and brought her back to Virginia. William advertised that he also repaired music boxes, clocks, and chronometers, which are precise timekeepers used aboard ships to determine longitude. The Harpurs remained there ten years and had two daughters, Isabella and Jane.

A job opportunity came up in Eliza’s hometown so they moved to Philadelphia in 1845. He expanded his skill set from repairing chronometers and watches to making them, and building a reputation for quality workmanship. William Jr. was born in 1856, and William Sr. eventually set up his own shop at 407 Chestnut Street.

A reclusive philanthropist now enters the story, as the city began preparations for the nation’s 100th birthday celebration in 1876. Henry Seybert never married and never had to work since he inherited a great deal of wealth. But it gave him no satisfaction. He grew increasingly disturbed by a verse from the Bible about the difficulty of a rich man entering Heaven. He was advised that his job, his real purpose, was to distribute his wealth to benefit others, and that’s what he did.

He proposed to the city that he would fund the cost of a new c lock and bell for the tower at Independence Hall, then known as the State House. The city accepted his offer, so Henry contracted with a New York foundry to make and install the bell. He then consulted with William Harpur, who was the Philadelphia representative for the Seth Thomas Clock Company of Connecticut.

lock and bell for the tower at Independence Hall, then known as the State House. The city accepted his offer, so Henry contracted with a New York foundry to make and install the bell. He then consulted with William Harpur, who was the Philadelphia representative for the Seth Thomas Clock Company of Connecticut.

William placed the order for a 6000-pound mechanism to run ten-foot dials on the four sides of the white steeple shown here. The brick tower beneath it had to be rebuilt to support the additional weight. The clock itself cost $6000, from which William made a commission of $575. Henry’s gift is still in operation today, where it has been chiming the hours every day since July 4, 1876.

William placed the order for a 6000-pound mechanism to run ten-foot dials on the four sides of the white steeple shown here. The brick tower beneath it had to be rebuilt to support the additional weight. The clock itself cost $6000, from which William made a commission of $575. Henry’s gift is still in operation today, where it has been chiming the hours every day since July 4, 1876.

William sold his building at 407 Chestnut in 1887 and moved to 10 South Fourth Street. Five years later as he walked home in the summer sun, his body’s mechanisms for dealing with heat were ![]() overwhelmed. He collapsed and died on the way to the hospital from heat stroke.

overwhelmed. He collapsed and died on the way to the hospital from heat stroke.

William Jr. continued the family business for many years. Eliza joined her husband in Section 43 in 1910, but the children were all buried elsewhere.

Support the Friends of Mount Moriah

Help us in our mission to restore and maintain the beautiful Mount Moriah Cemetery by donating to our cause or volunteering at one of our clean-up events.