Title: Army Privates, Civil War, Killed in Action

Birthdate: 1837-1840

Death Date: September 17, 1862

Plot Location: Section 58, Lot 5, SE corner

Tyson Evans shares almost all of the same biographical data as William Edwards except their birthdays. These two single white males joined Company A of the 72nd Pennsylvania Infantry on August 10, 1861 in Philadelphia. The 72nd’s “Muster Out Roll” shows they were both killed in the Battle of Antietam (as was nearly half of the entire regiment, according to some accounts) on September 17, 1862. They were both buried in Section 58, Lot 5 at Mount Moriah on October 4, although the death certificates say October 6. Sources differ on who was older but the cemetery register states that Tyson was 25 and William was 23.

It’s significant that they were returned for interment in their hometown, because thousands or even hundreds of thousands of Civil War soldiers were not. This 73-foot tall obelisk at the Antietam battlefield honors those buried there and all who served with the 72nd regiment along with the 69th, the 71st, and the 106th regiments, which together were known as “the Philadelphia Brigade.”

It’s significant that they were returned for interment in their hometown, because thousands or even hundreds of thousands of Civil War soldiers were not. This 73-foot tall obelisk at the Antietam battlefield honors those buried there and all who served with the 72nd regiment along with the 69th, the 71st, and the 106th regiments, which together were known as “the Philadelphia Brigade.”

It’s also significant that the residence address on each death certificate says, “Spring Garden Hose House,” another name for the Spring Garden Fire Engine Company #41. Evans and Edwards were firefighters before enlisting, and perhaps their fellow volunteers chose to honor them by arranging for their burial.

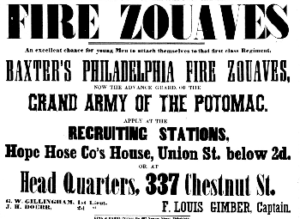

The 72nd was even known as the “Fire Zouaves” because most of the enlistees in this regiment were volunteer firefighters from Philadelphia and Delaware counties. They wore a somewhat splashy uniform of light blue trousers  and vest, dark blue jacket with 16 brass buttons and red trim on everything, along with white gaiters over their ankles.

and vest, dark blue jacket with 16 brass buttons and red trim on everything, along with white gaiters over their ankles.

Sadly, the markers for these two friends who shared so much together, including their sacrifice, have not been located.

Making the research into these two men more difficult was that there was another soldier from Philadelphia named William Edwards. He was also at Antietam and died that September, but he was in a different unit and died on different date.

The obituary for this other William Edwards ran in two Philly newspapers: “EDWARDS – Killed opposite Shepherdstown on Saturday, Sept. 20th, William Edwards, member of Company C, One-hundred and eighteenth Regiment PV, eldest son of the late Ann Edwards, aged 28 years.” He was probably buried near his place of death, since there was no mention of his burial place or date, and no Philadelphia death certificate or Mount Moriah Cemetery record was found.

His story, based on the documents found, begins with his enlistment date, August 5, 1862, which was almost a year after the friend of Tyson Evans. The 118th joined the Maryland campaign less than a month later with little training, and it was discovered that half of the weapons it was issued were defective.

The unit was held in reserve at Antietam, but joined other regiments the next day in pursuit of the Confederates. They crossed the Potomac into Shepherdstown in what is now West Virginia on September 20. The rookie unit exchanged fire for about 30 minutes but didn’t withdraw as soon as the order was given, as the other regiments did, so most of the casualties were from the 118th. Some were shot while trying to cross a dam, some drowned in the river, and others were killed by friendly fire because of their late retreat.

The likelihood of him being returned home was very slim, and even less likely that he could be in Mount Moriah, but apparently his family members are. A number of Edwards family burials, starting with his late mother, Ann, are in Section 7, Lot 10, grave 4. Cemetery records show her burial was October 14, 1859.

Pension records also brought some clarity. William Edwards of the 118th was, in fact, married because the record shows his wife, Eleanor, filed for his pension. Eleanor Bryan was buried in this plot in Section 7 after her death in 1909, having changed her last name after remarriage. Also buried here are their daughters: Sarah Jane Edwards died June 12, 1861 before she turned 3, and Annie C. Edwards was just 11 months at her death in May, 1862, three months before her father enlisted.

In order for William to be buried here the body would have to be located, identified, and an interested party would pay for transportation. More than 21,000 were killed or wounded after Antietam, but there were no rules for what to do with all those bodies, no ambulance corps, few if any coffins, and no distribution and transportation system. Most were buried where they fell, or nearby, in unmarked graves and to remain unknown. The enormity and immediacy of the task meant mass burial was the most efficient procedure.

Putting the carnage of the Civil War in context like this, returning the remains of the two men of the 72nd, William Edwards and Tyson Evans, was a rare and noble thing to do. As for the widow of William Edwards of the 118th, she had just lost both of her children within the past 15 months. She might not have known about or chosen to pay for a cenotaph, a marker that is placed in tribute to someone not actually buried there. The story of his life as reported here will have to do.

Support the Friends of Mount Moriah

Help us in our mission to restore and maintain the beautiful Mount Moriah Cemetery by donating to our cause or volunteering at one of our clean-up events.