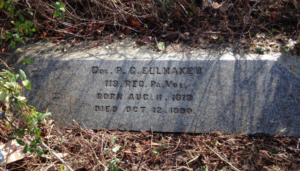

Title: Army Colonel, Civil War; early baseball club co-founder

Birthdate: August 11, 1813

Death Date: October 12, 1890

Plot Location: Section 11, Lot 17

The Ellmaker family’s roots go deep in Lancaster County and well before the Revolutionary War. Peter had a half-brother, Frederick, born in 1811 but their father died in 1816. That’s all that’s known of their home life, except that both boys graduated in 1826 from the Litz Academy for Boys in Lancaster. They must have traveled to Philadelphia together to start their working careers.

Their early occupations are unknown, but they both developed an interest in playing “town ball.” Also known as “cat ball” or “rounders,” it was the forerunner of today’s baseball, and became extremely popular as a club sport throughout the city in the 1820s. This is where Philadelphia began its love affair with the game for the past 200 years.

Peter and Frederick were among the organizers of the Olympic Club, the game’s first local team, founded in 1831.Two years later it merged with a group of Central High School graduates to form the Olympic Town Ball Club. They played at Broad and Wallace Streets in the Spring Garden section unless there was a game on Sunday. Pennsylvania’s “blue laws” prohibited certain activities on that day so the team would board a ferry to play in Camden.

In 1830 Peter joined the Washington Grays, also known as the “Volunteer Corps of Light Infantry” in Philadelphia. It was the precursor of the Pennsylvania National Guard, and was called up by the Governor to disperse a mob in Harrisburg in 1838. Six years later as a lieutenant, Peter and the Grays helped control a riot in Philadelphia where “nativists” were prejudiced against the influx of Irish immigrants and were threatening violence.

In 1841 he was appointed Naval Officer at the Port of Philadelphia by President William Henry Harrison. A Philly girl named Sarah Ann Wade became his wife for life in 1844 and they raised three children together. He remained a Naval Officer until sometime in the 1850s. Then, in the 1860 census, his occupation was listed as a notary public.

As the war with the South was brewing, Peter recruited young men to join the Washington Grays as a reserve guard for the protection of the city, and the Governor commissioned him as Colonel on April 21, 1861. In August of 1862 he organized the 119th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers. He led his 1200 troops in battle at Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and the Bristoe and Mine  Run Campaigns in late 1863.

Run Campaigns in late 1863.

This photo shows the monument at Gettysburg erected by the veterans of the 119th. Colonel Ellmaker resigned from his post in January of 1864 for reasons unknown, but he was honorably discharged.

While the Colonel was on the battlefield, his son, 17-year-old Thomas, answered the governor’s call for an emergency militia. It was in June of 1863 as Confederate forces were about to cross into the Keystone State. Since they were soundly defeated at Gettysburg the reserves were not needed, so the young Ellmaker was discharged after six weeks.

In the fall of 1865 President Andrew Johnson appointed Peter to the post of U.S. Marshall for the eastern district of Pennsylvania. A few years later he opened a shoe store, and from the mid-1870s until his death he was a bookkeeper and accountant.

He was a member of the Masonic Veteran Fraternity, and also the president of the Phoenix Volunteer Hose Company before it was replaced in 1871 by the Philadelphia Fire Department. During the Centennial Exhibition in 1876 he was superintendent of the employees.

There was a 50th Anniversary celebration of the Olympic Town Ball Club in 1883 that coincided with the opening of the club’s new grounds at 18th and Cumberland Streets. Peter was honored as one of the six co-founders who were still alive. (Frederick had died six years earlier.) Some of the younger members played a shortened game, followed by a reunion dinner where stories were shared and congratulatory remarks were made.

Peter suffered from an illness for most of 1890 before he died in October. In the will he wrote earlier that year, he specified that no public notice of his death be published, his funeral be “as economical as possible,” and his coffin and gravestone be without ornamentation. His estate’s appraised value consisted of $810 in cash. Sarah died 13 months later and her children placed a  somewhat more elaborate stone next to his.

somewhat more elaborate stone next to his.

Support the Friends of Mount Moriah

Help us in our mission to restore and maintain the beautiful Mount Moriah Cemetery by donating to our cause or volunteering at one of our clean-up events.