Title: Army musician, Civil War; physician/druggist

Birthdate: July 31, 1843

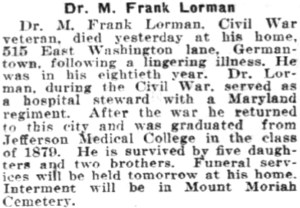

Death Date: October 13, 1923

Plot Location: Section 151, Lots 55 & 57

Loman and Lohman were spelling variations of the Lowman name that was used by Matthew’s father and grandfather. Less common names for Matthew were M. Frank, Frank, M.F. and his given name, Matthias. His father lived most of his life as a shoemaker in Elkton, Maryland where Matthew and four brothers grew up, and all of them changed their surname to Lorman.

Although Maryland was a slave state, it didn’t secede from the Union and most of its young men joined Union regiments. The 5th Maryland Volunteer Infantry needed a drummer, as most units  did, so Matthew became one of the regiment’s musicians when he signed up on October 5, 1861. (There was most likely a bugler as well.) His younger brother, John, also played a drum like this when he enlisted in 1864.

did, so Matthew became one of the regiment’s musicians when he signed up on October 5, 1861. (There was most likely a bugler as well.) His younger brother, John, also played a drum like this when he enlisted in 1864.

Drummers did more than keep time as the unit marched. They had to learn dozens of drum calls, and the playing of each call would tell the soldiers the specific task they were required to perform. Drummers didn’t carry weapons, but had other jobs like helping to carry men away from battle and assisting in makeshift field hospitals. Some had to hold down patients during amputations and even dispose of the limbs.

One source says he was promoted to “hospital steward” in October of 1862. On November 8, however, he was brought to an army hospital on Broad Street in Philadelphia as a patient. After 60 days he was given a disability discharge and a diagnosis of nephritis, or kidney disease.

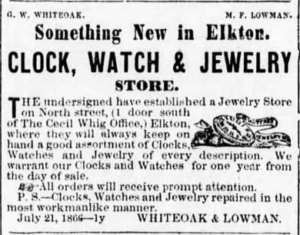

While that was his first exposure to the gritty side of healthcare, it was years before he would make  it his career. This 1866 newspaper ad shows his partnership in a jewelry store in Elkton, with the same name he used in the military, Lowman.

it his career. This 1866 newspaper ad shows his partnership in a jewelry store in Elkton, with the same name he used in the military, Lowman.

Three weeks after this was printed he married Sarah Katherine Simpers in her geographically descriptive hometown of North East, Maryland. Four months after that, their son William was born. After another two years the partners opened a second store 60 miles south in Denton, Maryland.

The first of five daughters joined the family in 1869 after they moved in with Matthew’s brother, John, in Elkton. Two more were born as Matthew considered changing careers to provide for the growing family. They headed north to Philadelphia in time for the 1876 Centennial celebrations. At that point he followed his brothers in using the Lorman surname. The last two girls were born while Matthew was enrolled in Jefferson Medical College. He graduated in 1879 and henceforth called himself either a physician or druggist, or both.

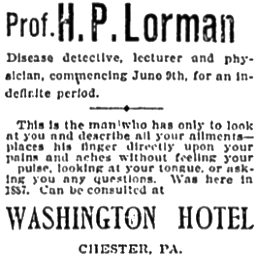

While he was considered a legitimate physician, many in those days were not, like his brother Henry. With no formal training on record, he concocted “patent medicines” and set himself up as “Professor H. P. Lorman, the Indian Doctor” although he was neither. Typical of the “snake oil  salesmen” of that era, he sometimes had singers and other entertainers travel with him to small towns and draw a crowd. Then he would sell his elixirs and leave town, usually just one step ahead of the law.

salesmen” of that era, he sometimes had singers and other entertainers travel with him to small towns and draw a crowd. Then he would sell his elixirs and leave town, usually just one step ahead of the law.

Henry came up with his new career just as Matthew was building his. Could he have learned about making some simple herbal tonics from his college-educated brother? There’s no known connection, but it was a lucrative business. Henry admitted to a reporter in 1887 that he made $18,000 in the past year selling his “Indian Oil.”

Matthew chose to build his “brick and mortar” business at 15th and Dickinson Streets in Point Breeze, with their son William as a clerk. He married at age 22 but died at 25 of pneumonia and was buried in Maryland in 1892. When Matthew’s wife died five years later, he bought Lots 55 and 57 in Section 151 at Mount Moriah. The intent was to provide for his five daughters as well, four of whom would later make that their resting place.

In another plot twist, Matthew engaged in the lumber business in Jamaica in the 1890s. A newspaper report in 1898 said he had been spending three months there every summer and was going again despite the Spanish-American War being waged in Cuba. He was even a candidate at one point to be appointed Consul to Jamaica. How this part of his story concluded remains a mystery.

For Matthew to set himself up as both doctor and druggist wasn’t unusual. Physicians typically kept a supply of simple medications for common problems, but relied on trained pharmacists who specialized in mixing or compounding certain powders or elixirs. Matthew apparently felt competent enough to do both, and there were no laws against it.

Neither were there any laws to protect consumers from entrepreneurs like “Professor Lorman.” Many of those purveyors of potions went out of business after the Pure Food and Drugs Act was passed in 1906. It set regulations for labeling medications and created what would become the Food and Drug Administration.

By 1900 Matthew was still supporting four single daughters in their twenties, with just one holding a job. Three of them eventually married. The one who didn’t was able to convince her father to move with her to her sister’s home in Germantown. That probably happened before World War I, but it must have been hard to leave the neighborhood where he made a decent living for 30 years.

By 1900 Matthew was still supporting four single daughters in their twenties, with just one holding a job. Three of them eventually married. The one who didn’t was able to convince her father to move with her to her sister’s home in Germantown. That probably happened before World War I, but it must have been hard to leave the neighborhood where he made a decent living for 30 years.

His tenure in the field was a time of great medical advances like the marketing of aspirin in 1899, the role of nutrition, and improving sanitation to prevent disease. Matthew still listed his occupation at his new residence as a physician, according to the 1920 census, but times were changing. His daughters and grandchildren helped him celebrate his 80th birthday in the summer of 1923. They had to say their final goodbyes after his heart stopped beating just ten weeks later.

Support the Friends of Mount Moriah

Help us in our mission to restore and maintain the beautiful Mount Moriah Cemetery by donating to our cause or volunteering at one of our clean-up events.