Title: Lawyer, educator

Birthdate: May 5, 1849

Death Date: May 26, 1934

Plot Location: Section 140, Lot G

This ancient Irish surname is pronounced like Mars but without the letter “s.” John was given the name when he was born in Waterford, Ireland, but his father wasn’t there at the time. Thomas Maher was one of the Young Irelanders, a group of political activists who attempted an insurrection in 1848, partly due to the potato-blight famine. Facing arrest for his participation, he sailed to New York and arrived one month before John’s birth. He sent for his wife and four children in 1851.

The family settled in New Jersey where three more children were born. Due to an unknown illness, John lost his eyesight or almost all of it when he was seven years old. At age 15 he entered the Pennsylvania Institution for the Instruction of the Blind which was in Philadelphia. There he learned how to succeed despite his handicap.

Learning Well & Doing Good

The University of Pennsylvania accepted him in 1870 at age 21 and he not only succeeded, he  conquered. John graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in 1874 and ranked first in his class. He was a member of Penn’s oldest student group, the Philomathean Society, a literary society where he was the winner of the senior debate.

conquered. John graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in 1874 and ranked first in his class. He was a member of Penn’s oldest student group, the Philomathean Society, a literary society where he was the winner of the senior debate.

What probably meant even more to him was when he co-founded the Friedlander Union in 1870, a mutual aid society where all members were blind except the secretary. It was named after the founder of the school John attended as a teenager. He served as president for a time, and was still active 20 years later as the treasurer.

John earned his Master’s degree in 1877, followed that same year by his marriage to Bella Milsted. She was about 37 years old and the marriage never produced any children. He was listed in the 1880 census as a school teacher. Other sources say he was a private tutor in math and English around that time.

City directories in the 1880s listed him as a linguist, and he excelled in Latin. He knew it well because he returned to Penn to study law and received his L.L.B., or Bachelor of Laws degree, in 1891. Shortly after opening his law practice he was also appointed as an examiner in Latin for candidates who wished to work for the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania.

As the new century was approaching, Philadelphians were looking forward to having their new city hall completed. New, electrically-powered trolleys were already replacing the horse-drawn streetcars. John had achieved great things in spite of his visual impairment. His success dispelled the misconception that he and those like him should be pitied, dismissed as incapable, or otherwise be victims of discrimination.

Tragedy, Troubles, and Teaching

His ability to overcome, however, was put to severe testing as the old century ended. His mother died in 1897 followed by his father in 1898. His wife died in 1899, and a brother in 1900. He began to understand something of “the suffering of Job” in dealing with such sudden loneliness. All four were buried in New Jersey, and he had to carry on by himself.

He was 54 in 1903 when he married Emmy Clara Himmelsbach, a 28-year-old music teacher. She promptly gave birth to John Jr. (1904-43), Thomas (1905-68), Emmy (1907-65), and Frederick (1908-66). They bought a home in Lansdowne in Delaware County. John continued his law practice but also returned to his love of teaching, opening a prep school where he tutored children of many prominent and wealthy families.

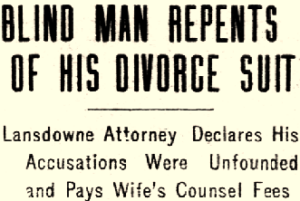

Trouble quickly followed when John moved out and filed for divorce in 1909, claiming infidelity on Emmy’s part with a former pupil. He soon withdrew his request but because he left, she went to the Desertion Court, which  ordered him to pay her $16 a week plus the mortgage on the house. John had the alimony reduced to $12 in 1910 and to $8 in 1914.

ordered him to pay her $16 a week plus the mortgage on the house. John had the alimony reduced to $12 in 1910 and to $8 in 1914.  He complained of ill-health and having to sell stocks and mortgage his property while Emmy was now herself a private tutor at Lansdowne High School.

He complained of ill-health and having to sell stocks and mortgage his property while Emmy was now herself a private tutor at Lansdowne High School.

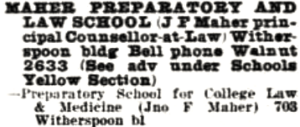

While Emmy listed herself as married on the 1910 and 1920 census, John called himself widowed and they never reconciled. He lived in boarding houses in the area around 45th and Baltimore Avenue near Clark Park. More time was spent on his prep school, renting office space in the Witherspoon Building at 13th & Market St. In the next few years the school had a more sophisticated  title, the “Maher Preparatory School for College Law and Medicine,” or variations thereof, as shown in this 1918 city directory listing.

title, the “Maher Preparatory School for College Law and Medicine,” or variations thereof, as shown in this 1918 city directory listing.

Soon his children were teenagers and John was in his seventies. All four children lived out their entire lives in Delaware County, and one even became a lawyer, like his father. None of them were buried at Mount Moriah.

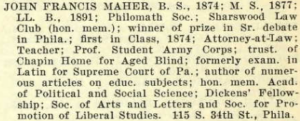

Exactly when John stopped his school and law practice is a mystery, but in 1918 he also taught  for the government. This alumni directory published by Penn in 1922 summarizes his accomplishments, one of them being a professor with the Student Army Training Corps. The War Department started the program in 1918 to teach various skills needed for the war effort. Penn was one of 157 campuses that participated and hired John to be an instructor, although it lasted less than a year.

for the government. This alumni directory published by Penn in 1922 summarizes his accomplishments, one of them being a professor with the Student Army Training Corps. The War Department started the program in 1918 to teach various skills needed for the war effort. Penn was one of 157 campuses that participated and hired John to be an instructor, although it lasted less than a year.

Doing Good, Again

Another one of John’s proudest accomplishments occurred around 1906. Twelve working blind men (and former pupils of the school for the blind) saw a need for a home for the elderly who were blind. No such non-sectarian home existed anywhere in the region. John was most liekly one of those 12, and served many years on the Board of Trustees of the Chapin Memorial Home for Aged Blind. It was incorporated in 1909 and named after William Chapin, the former principal of the school for the blind.

By 1930 John was finally living in his own home near 43rd and Woodland with a live-in housekeeper. Two years later, at age 83, he was one of the  residents of the Chapin Home at 6713 Woodland Ave. Once again he stated he was widowed (perhaps, by implication, from his first wife). The cause of death was heart failure, with the administrator of the home signing his death certificate.

residents of the Chapin Home at 6713 Woodland Ave. Once again he stated he was widowed (perhaps, by implication, from his first wife). The cause of death was heart failure, with the administrator of the home signing his death certificate.

What worldly wealth he had was given to the home, which paid for his grave not far from the Naval Plot at Mount Moriah. Emmy lived her last years with her daughter and was buried in her parents’ plot at Fernwood Cemetery in 1948.

Support the Friends of Mount Moriah

Help us in our mission to restore and maintain the beautiful Mount Moriah Cemetery by donating to our cause or volunteering at one of our clean-up events.