Title: Saw factory foreman

Birthdate: December 22, 1926

Death Date: February 26, 1896

Plot Location: Circle of St. John, Lot 3, Division E, northeast corner

The cradle grave, shown here, was a popular choice in the late 19th century, which featured space for a flower garden within its borders. This story is taken from a biography written by Laurel McCulllough, who has worked to restore many of these graves at Mount Moriah and researched several of the lives represented by these memorials. A column in the March 2, 1896 edition of the Philadelphia Times is also referenced.

It’s impossible to tell David’s story without including Henry Disston, a famous Philadelphia industrialist. Henry Disston emigrated with his father and sister from England in 1833, but his father died within three days of his arrival. Bereft at the age of 14, Henry apprenticed himself to a group of resident English saw makers. When they went bankrupt about 1840, his apprenticeship ended and they let him go with saw making materials and tools worth about $350.

Henry took what he had, set up a furnace in his home, and started making tools that year. At age 21, his first employee was the apprentice David Bickley, who was 14. About this same time, Henry married Amanda Mulvina Bickley. Born in 1823, there is a presumption that she was David’s older sister and the men were actually brothers-in-law. Years later, David named his first daughter after her, and his eldest son gave his daughter that same name.

Making saws required a high level of craftsmanship. Almost all early American saws were imported, particularly from Sheffield, England until about this period of time. David recalled those early days when he was interviewed in 1890:

“The business was carried on in the back room of a building [near] Arch Street, below Second. There were just the two of us, and in that little room all the work was done. In those days, the grinding was not done by the maker, and I have often taken a wheelbarrow, loaded with saws, and wheeled it out 2nd Street to Kensington, to the grinders. At that time, a good workman did well in the smithy if he turned out one dozen saws a day; now, with the improved methods and machinery, a man turns out 15 dozen a day and does not work as hard.”

David also noted that they actually did not produce any saws at all in the first two years, just masons’ trowels and cleavers. He also recalled walking over a mile every morning to the wharf on the Delaware to obtain a wheelbarrow’s worth of coal to feed the forge for the day. Henry didn’t have the cash flow to afford larger quantities.

A personal tragedy struck during those first two years. Amanda Disston was pregnant with twins, but they died after a premature delivery. Then Amanda died six days later.

Henry struggled through that as his business struggled. He moved to the corner of 3rd and Arch Streets and things improved after a few years. David completed his apprenticeship and became a journeyman in 1848. He stayed with the shop but never became a partner, and there is no indication he was ever offered the opportunity. But he did become a partner for life with a woman named Elizabeth when he married her that same year.

A fire at the shop caused a setback but created an opportunity. Henry built a new factory and by 1850 he was employing 65 men. David’s family grew as well, adding Frederick J. Bickley that year and three more over the next six years. David also learned the value of thrift from his boss. He opened an account with the Philadelphia Savings Fund Society that same year. Elizabeth opened her own account in 1856.

By 1855, Henry Disston became the first saw manufacturer to develop a method of producing his own steel, mainly from waste products. By the 1860’s he was the most successful saw manufacturer in the United States. He made huge profits supplying steel products to the Union Army during the Civil War. Over the next half-century, Disston was the leading saw maker in the world. By the 1940s, it was estimated that 75% of all hand saws sold in the U.S. were made by Disston. (They’re still made and sold today at all major hardware retailers and online.)

Returning to David’s story: he had a very limited involvement with the Civil War. A call went out from the Governor in June of 1863 for an emergency militia to defend the state from the rebel invaders as they advanced toward Gettysburg. Both he (as a private) and Henry (as a sergeant) joined the 40th Militia Infantry on July 2 and were kept on reserve until their discharge on August 16.

Returning to David’s story: he had a very limited involvement with the Civil War. A call went out from the Governor in June of 1863 for an emergency militia to defend the state from the rebel invaders as they advanced toward Gettysburg. Both he (as a private) and Henry (as a sergeant) joined the 40th Militia Infantry on July 2 and were kept on reserve until their discharge on August 16.

David’s namesake son was born in 1862 while the family was living north of Center City in the Northern Liberties section, later moving to 1227 North 2nd Street. In the 1870s Henry began moving his operations to a new facility located along the Delaware River in the Tacony section of the city. This complex was their major production center for 80 years.

The Industrial Revolution brought about labor unrest and unionization, but Henry had a paternalistic style of leadership. His care for his workers was demonstrated by excellent wages and even health care. When he moved to Tacony, he purchased over 300 building lots and constructed some 600 twin homes for his workers which he either sold or rented to them. He wanted a wholesome environment, banning bars and immoral amusements, which led to the blossoming of the Tacony area of northeast Philadelphia. Today Disston Street runs from Disston Park next to Interstate 95 across the city to Cheltenham.

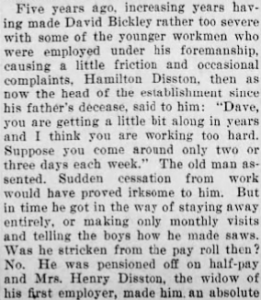

David had risen to the position of foreman in charge of the long saw department. In 1881, three years after Henry died, David’s department moved to Tacony but he chose to remain in Kensington and make the commute. Fred and Amanda had married but the others were still living at home. All three sons made their careers as saw makers.

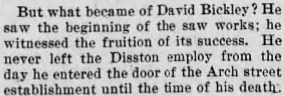

David’s beloved Elizabeth died in May of 1890. This story from the Times recounts how David was treated with respect and dignity in his last years.

That 21-year-old employer made his best business decision when he hired that 14-year-old apprentice. The business grew to include 38 acres, 21 buildings and 1700 employees when the faithful employee died. David left a meager estate compared to his boss, just $8700, with most of that in stocks. More important to David was his good life with his good wife and five conscientious and responsible children.

Support the Friends of Mount Moriah

Help us in our mission to restore and maintain the beautiful Mount Moriah Cemetery by donating to our cause or volunteering at one of our clean-up events.