Title: Gangster

Birthdate: September 12, 1899

Death Date: August 7, 1934

Plot Location: Section 1, Lots 89 & 91

Anthony’s parents married in 1894 and sailed from Italy to New York that same year. He was the firstborn of 13 children in the Zanghi home. Nine of them lived to adulthood and five of those were girls. The first four children were born in New York but by 1907 they were living at 838 Montrose Street in the Italian section of Philadelphia. Giacomo Zanghi was a baker and eventually owned his own pastry shop.

When the United States entered the Great War in 1917, the Selective Service Act required the registration of young men in three stages. For 18-year-olds like Anthony, the date was September 12, 1918. The fighting stopped less than two months later so he wasn’t called to serve. The 1920 census shows he was still at home but not employed, or at least not in a lawful occupation.

Charting the course of one’s life ultimately comes down to making decisions and reaping the benefits or consequences. It’s not documented that Anthony joined a gang as a teenager but he was leading one in his 20s, and was known by the nickname “Musky.” This was the decade of Prohibition, and liquor trafficking seemed to be the easiest way to get rich.

The Gang Leader

By the mid 1920s he bought a restaurant that served as his cover, the La Tosca Cafe at 9th and Fitzwater Street. Musky probably had just a small gang of four or five, mostly involved in gambling and bootlegging. (His teenage brother Vincent may have been one of them, but he was sent to prison in 1926 for robbing a bus.) Musky tried to muscle his way into the action at bars and speak-easys. That put him in as much trouble with his competitors as he was with the police.

Salvatore Sebella was said to be the first mob boss of the La Cosa Nostra family in Philadelphia, and he decided he had enough of Musky. He set up a drive-by shooting on May 30, 1927. His men were in place as his target was finishing his dinner at the Cafe Calabria at 824 South 8th Street.

Musky left and stood outside to talk with his younger brother Joseph, 19, and colleague, Vincent Cocozza, 31. Gunmen appeared on the sidewalk and started shooting just as a passing blue sedan also opened fire, then carried the shooters away. The only one not killed was Musky, who managed to find cover just in time.

One of Musky’s employees happened to be leaving a cigar shop down the street when the shooting started. Piero Francisco came to America from Italy in 1926 with a dance partner, hoping to make it to Hollywood. After his partner died at sea and not knowing English, Piero came to the Italian quarter where Musky hired him to entertain the customers.

Not far from him was six-year-old Freddy Cocozza who saw his uncle fall dead. He grew up to have a career as a famous singer under the stage name Mario Lanza.

The Stool Pigeon

What happened next was unprecedented: the underworld’s “code of silence” was broken when Musky “squealed” on the mafia. For the first time in police history gangland members were fingered by one of their own. The next day six men were identified in a lineup. Musky yelled at them and even got in a punch at Salvatore Sebella.

He later cried openly, saying, “I’ll be killed now for sure, but I don’t care. My brother is dead!” He had another reason to weep because he knew his brother’s wife was about to have a baby with no father. Joseph Zanghi Jr. was born exactly one week later, then died from tuberculosis 17 months after that.

The wheels of justice moved much faster in those days, because just two weeks later the first trial began but without the state’s star witness. Word on the street was that Musky was offered $50,000 to disappear, and he did.

weeks later the first trial began but without the state’s star witness. Word on the street was that Musky was offered $50,000 to disappear, and he did.

The Other Eyewitness

Piero was called to testify. One reporter noted, “His account of the double murder was clear cut and unshaken on cross examination.” Naturally, his life was suddenly at risk. He was fired upon as he walked to City Hall the first day, and his apartment building caught fire a few days later. The judge had him taken into protective custody at the House of Correction (now Riverside Correctional Facility). Musky later reappeared and was placed there as well.

That first trial was the only one to successfully send one of the accused to prison. Some of the others were acquitted or their trials were indefinitely and mysteriously postponed. The two witnesses remained in custody a total of 20 months.

After living for three years in America (and over half of that time in prison) Piero Francisco had saved enough money to go back to Italy. In March of 1929 a newspaper reporter wrote that detectives served as his escorts but wouldn’t reveal the day he left or the ship. He told reporters he just wanted “to live quietly under Italy’s Fascist regime,” having had his fill of “America’s gangland entanglements.”

Musky had his fill of Philly and left for New York under the name William Martino. He found a partner, Anthony Cugino, who was known in Philly’s underworld as Tony Stinger. He was first incarcerated at age 12 and had such an itchy trigger finger he would eventually be linked to ten murders. The two Anthonys began operating a counterfeiting business.

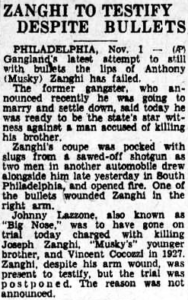

After three years Musky returned to Philly to again seek justice for his dead brother, as described in this November, 1932 news story. It also reveals his intention to marry, since his fiancée had given birth a few months earlier.

The Family

Antoinette Alice Giunta LaFauci was a Philadelphia widow with four children when Gloria Zanghi was born in June. The next year she had twin girls, followed by Anthony Raymond Zanghi in September of 1934.

However, the boy never knew his father. He was born one month after Musky was murdered in Manhattan’s Little Italy neighborhood. Anthony Cugino argued with him about their money racket and to settle the disagreement he riddled him with bullets.

Four months later, in the midst of raising seven children under the age of 8, Antoinette was arrested for passing her husband’s fake bills. She wasn’t a hardened criminal, however, just a mother trying to put food on the table. She had continued to operate a fruit store Musky owned at 9th and Montrose Street and tried to unload some of the phony bills that were left after his death.

She was convicted in March, 1935 and given five years probation. All seven children, 17 grandchildren, and 13 great-grandchildren were alive when Mrs. Anthony Zanghi died in 1984.

Police tracked down Anthony Cugino by September of 1935. The four-state manhunt gave him the title of the East Coast’s Public Enemy #1. He hanged himself in jail a few days later, before he could be arraigned.

Where Antoinette buried her husband may not have been coincidental after consulting with her Catholic mother-in-law and other family members. Anthony Salvatore Zanghi was the only member of his and her family not buried at Holy Cross Cemetery, which is owned by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Philadelphia.

Support the Friends of Mount Moriah

Help us in our mission to restore and maintain the beautiful Mount Moriah Cemetery by donating to our cause or volunteering at one of our clean-up events.