Title: Volunteer Civil War nurse

Birthdate: December 6, 1821

Death Date: May 27, 1864

Plot Location: Section 27, Lot 119

This four-word epitaph, Volunteer Civil War Nurse, does well on the surface to summarize this person’s great achievement. Before looking closer at her life, two other women of the Antebellum era should be briefly considered: Florence Nightingale (left) and Clara Barton.

The first, born in 1820, was the founder of modern nursing, the second, born the same year as Mary, was the founder of the American Red Cross. The first became well known for working in Europe during the Crimean War in the 1850s, the second in the U.S. Civil War in the 1860s. While these pioneers cast a much wider net in their service to others, Mary shared equal zeal for comforting the sick while also being an attorney’s wife and mother of four boys and two girls.

Most sources confirm the birth and baptism of Mary Ann Parker Sharp was in Lancashire, England, and she became Mrs. Edward Brady in Manchester in 1846. They made Philadelphia, Pennsylvania their home the following year when their first of six children arrived. All of them were baptized at St. Mary’s Protestant Episcopal Church at 39th and Locust Streets.

Her youngest child was two years old when Mary felt a heavy burden for the thousands of soldiers injured or sick as a result of the “War of the Rebellion,” and in particular, the Peninsula Campaign of 1862. The Army of the Potomac pushed north from Norfolk in a failed attempt to capture Richmond, resulting in over 23,000 Union troops killed or wounded.

The worst cases were treated locally in field hospitals but an influx of the sick came as far north as Philadelphia. The  government built 24 military hospitals there, including the 4500-bed Satterlee Military Hospital complex, shown in this drawing. It was at 44th and Pine Streets, which wasn’t far from Mary’s house. Patients needed food, bandages, medicine, clothing, socks, and someone who would write a letter, lend an ear, and offer comfort.

government built 24 military hospitals there, including the 4500-bed Satterlee Military Hospital complex, shown in this drawing. It was at 44th and Pine Streets, which wasn’t far from Mary’s house. Patients needed food, bandages, medicine, clothing, socks, and someone who would write a letter, lend an ear, and offer comfort.

Mary called a meeting of her friends on July 28, 1862 at her husband’s law office to see what could be done. That was the first meeting of the Ladies Association for Soldiers’ Relief, also known as the Soldiers’ Aid Association, of which she was chosen president. As a biographer wrote of her, “From that day to the hour of her death –not quite two years after — her labors were unceasing, her devotion unbounded, and her discretion unerring in the great enterprise of the sanitary well-being of the soldiers of the republic.”

There was no health care “system” in those days, so similar soldiers aid societies were being organized in both the North and the South because of the bloodshed. Another relief group was established by the Society of Friends (Quakers) that same year in Philadelphia, and many others rose to the occasion. Mary and her friends solicited donations, found a storage location for amassing the goods, and enlisted volunteers who could knit, bake, wash, or make whatever visits they could, as often as they could, at Satterlee and other hospitals in the city.

Meanwhile, Florence Nightingale published her 1859 book, Notes on Nursing: What it is and What it is not. It became a guide for many of these societies, and was widely read in convents where nuns were promptly dispatched to practice their newly-learned nursing skills.

The infrastructure was well in place by the end of 1862 and their attention was turned to the desperate need for supplies closer to the front lines. While other groups concentrated on local needs, Mary’s group entrusted her with the task of taking a wagonload of goods to Alexandria as Confederate troops advanced into Northern Virginia in 1863. She reported that she found the 40 military hospitals in the Washington, D.C. area housing 30,000 sick and injured, and another 20,000 were in sick camps farther west. It was certainly more than her organization could handle but they did what they could, and sent Mary on a second trip. The society ramped up its efforts, especially in May when fighting in Chancellorsville led to another 10,000 wounded.

Fortunately for Mary, her husband’s practice afforded them the luxury of having servants and a nanny for the children. She made a third trip south in May and another to Gettysburg in July, equipped with two camp stoves and more provisions. She found volunteers to help her cook during the day and build morale at night. She realized what she could not do for them medically she could do emotionally, often quoting Proverbs 17:22, “A merry heart does good like medicine.”

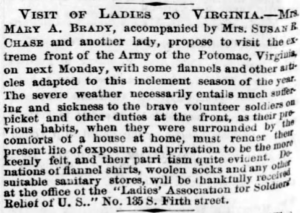

The Soldiers Aid Association continued to collect and distribute what was needed, and had great success in raising money as well. Mary discreetly disbursed some of the funds to widows of the  fallen. In January, 1864 another expedition was made to Virginia, as described here. She came home in February totally exhausted. Doctors found heart disease or, as described at the time, “an affection of the heart, rapidly developed by the last few weeks of uncommon excitement and fatigue.”

fallen. In January, 1864 another expedition was made to Virginia, as described here. She came home in February totally exhausted. Doctors found heart disease or, as described at the time, “an affection of the heart, rapidly developed by the last few weeks of uncommon excitement and fatigue.”

Mary fully intended to make another trip to Virginia in April but her condition was terminal. She suffered bravely in bed until her heart failed on May 27. The official cause of death was hydrothorax. She was eulogized as one “who followed closely in the steps of Him who always went about doing good, and reproduced the virtues of that Scripture heroine, the woman that was ‘full of good works and alms-deeds, which she did continually.’”

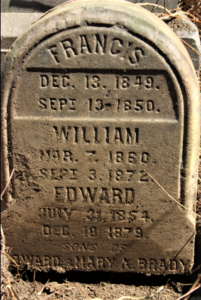

Edward chose a hillside plot at Mount Moriah for the family. He also had the remains of their second son, who died at nine months old in 1950, placed with his mother. The child had originally been interred in the graveyard at St. Mary’s Church.

In 1997 the 28th Pennsylvania Historical Society held a commemorative ceremony for Mary. The gravestone pictured above was provided by them and the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War because it was thought she might have been buried  without one. About 15 years later, volunteers with the Friends of Mount Moriah Cemetery discovered her original stone, along with one for Edward and one for three of their children. The stones were re-erected over their graves just below her modern stone.

without one. About 15 years later, volunteers with the Friends of Mount Moriah Cemetery discovered her original stone, along with one for Edward and one for three of their children. The stones were re-erected over their graves just below her modern stone.

(There is one other detail: the birth date on Mary’s original stone says 1821 and the new one says 1822. All that is currently known is that one of them is correct.)

It was especially fitting that Edward chose that hillside plot. It happens to overlook a section of the cemetery containing 402 military graves known as the Soldiers’ Plot, symbolic of Mary’s concern for and commitment to all those who suffered in the service of their country.

Support the Friends of Mount Moriah

Help us in our mission to restore and maintain the beautiful Mount Moriah Cemetery by donating to our cause or volunteering at one of our clean-up events.