Title: Army Sergeant, Civil War; bricklayer, pigeon fancier

Birthdate: December 27, 1836

Death Date: February 19, 1906

Plot Location: Section 128, Lot 55

John was a bricklayer his entire working life, aside from his military service. Street after street of similar-looking houses with brick exteriors, called “row houses,” were being built in South Philly to meet the need for housing due to an influx of immigrants. A famine in Ireland during the 1840s sent one million of its citizens to America during that decade alone, many of them arriving in John’s neighborhood, known as Point Breeze. That population boom caused a housing crunch, and it meant John had a steady income.

One of those Irish immigrants, his 18-year-old sweetheart, Margaret Dever, walked the aisle to become his bride. That was on August 16, 1859 at Ninth Presbyterian Church when John was 22. Two years later, the citizens of Philadelphia began to rally behind the Union in putting down the rebellion of the southern states. Over 100,000 patriotic young men of the city served in the Army between 1861-65.

Enthusiasm wasn’t as high in other parts of the country. As a result, a federal mandate in 1863 required its male citizens to register for “conscription.” The wealthy could pay $300 for an exemption, which was an average worker’s salary for an entire year. Black men were exempt because they weren’t citizens. Public outrage swelled, especially among the Irish in New York City where the worst rioting took place. Hundreds were killed and 3000 people of color were left homeless. An army general had to be sent to Philadelphia to suppress any outbreak of violence, which was rampant across the state.

John managed to avoid the draft for several months. Then he decided to volunteer on February 23, 1864 for three years. Why? Most likely because he was offered a $360 “bounty” or bonus for enlisting. Patience paid off. Private Love was assigned to Company M of the 3rd Regiment, Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery. He served in the long, difficult battle for Petersburg and Richmond in the summer, fall, and winter of 1864-65, and was promoted during that time to Sergeant.

After General Lee’s surrender in April, the 3rd Regiment was stationed at Fort Monroe, Virginia with the mission of guarding some political prisoners, and specifically to ensure that they ate, made no escape attempt, and didn’t commit suicide. Family lore says John was one of those men assigned to guard Jefferson Davis after Davis’ status was reduced from President of the Confederate States of America to Prisoner of War.

Unfortunately, Sgt. Love soon had his own status reduced. For two days, September 13 and 14, the record stated he was “so drunk as to be unable to perform properly his duties as a soldier” and was AWOL on September 16. He was put on trial before a “general court-martial” on September 22. A sentence following conviction could include demotion, losing up to a month’s pay or spending up to a month in prison.

John was given a reduction in rank to private. As events would unfold, the remaining companies of the 3rd Regiment were “mustered out” of the Army on November 9, 1865, and it couldn’t have come at a better time for the now-Private Love.

He had been given a furlough in February as part of his promotion to Sergeant, and during this time at home their first child was conceived. Years later, documents show their son, William John Love died of scarlet fever on December 30, 1869, at age 4. No birth certificate was found, but a birth in either November or December of 1865 fits the timeline. Another son was stillborn, a third died of typhoid fever, but two sons and a daughter lived to adulthood.

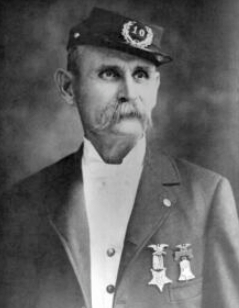

The studio portrait of him, above, was taken when he was 68, about the time of his daughter’s wedding in 1905, and less than a year before he died. Why is the “10” on his cap and what are the medals for? He didn’t get them while he was in the Army.

They represent his membership in a fraternal organization for veterans, The Grand Army of the Republic, which was formed in 1866. There was no Veterans Administration, no pension benefits, no rehabilitation, mental health or social services. The GAR became a powerful advocacy group. By 1890 they had over 400,000 members.

They represent his membership in a fraternal organization for veterans, The Grand Army of the Republic, which was formed in 1866. There was no Veterans Administration, no pension benefits, no rehabilitation, mental health or social services. The GAR became a powerful advocacy group. By 1890 they had over 400,000 members.

They also helped establish “Decoration Day” which became known as Memorial Day. Members belonged to local posts, and John was in the John T. Greble Post #10. That explains the “10” on his cap. Annual reunions were held, called “encampments,” and Philadelphia was host to the 33rd such event in 1899. John’s other pin is just a fancy “official souvenir” from that event, shown here. The design was based on the Liberty Bell, an image synonymous with Philadelphia.

“official souvenir” from that event, shown here. The design was based on the Liberty Bell, an image synonymous with Philadelphia.

Thanks to the influence of the GAR, Congress passed the Disability Act of 1890 to provide pension benefits to veterans who could prove at least 90 days of service in the Civil War and a disability not caused by “vicious habits,” even if unrelated to the war. It also extended pensions to widows and dependents of deceased veterans. John was awarded this benefit after providing a doctor’s statement, and after he died, his widow applied for and was given a small pension.

In addition to his GAR activity, in 1878 John joined a handful of people who were breeding and racing homing pigeons. Twenty years later he was acknowledged as a pioneer in the sport, which included thousands of birds and those who raised them around the country. Some of his “homers” could travel 500 miles in one day.

He was known nationally as an official with the Federation of American Homing Pigeon Fanciers, raising the profile of the sport and the value of these birds. In fact, ten years after his death, about 100,000 of them were put to use as messengers in World War I. His grand-nephew, John Love Leonard, served in that war and is also buried at Mount Moriah. His Notable life story can be found here.

Support the Friends of Mount Moriah

Help us in our mission to restore and maintain the beautiful Mount Moriah Cemetery by donating to our cause or volunteering at one of our clean-up events.