Title: Army Saddler, POW, Civil War; shoemaker

Birthdate: June 8, 1837

Death Date: March 31, 1895

Plot Location: Section 1, Lot 43, north half

Like thousands of other Irish families, the widespread famine of the 1840s pushed the Osbornes to find hope in America. Hugh was 11 when he and his parents left their homeland, but they brought a dozen other Osbornes from the extended family with them, landing in 1849. They settled in Philadelphia where father William was a butcher. Hugh learned a trade using another part of the animal called cowhide as shoemaking became his life’s work.

The internal conflict in Ireland was nothing like what came upon his new country in 1861. Hugh joined the First Pennsylvania Artillery that April for a three-month enlistment that took him to parts of Virginia and Maryland. Then the War Department allowed the regiment’s term to expire and the men returned to Philadelphia. A month later, he joined Company B of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

The difference between infantry and cavalry is, of course, horses, which means time and effort and money involved. Because of Hugh’s experience in working with leather, he was promoted to the rank of Saddler. (Like shoeing-smiths, wheelers, and some other trades, this was a specialty rank that came with a higher rate of pay.) A soldier in this position kept the harness, straps, and other leather items in good repair and was responsible for the stitching tools and supplies that were needed.

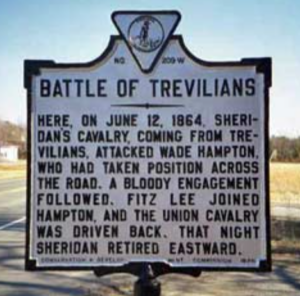

The 6th was in the major battles of 1862-63, including Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg, but the turning point for Hugh was a little-known skirmish near a rail line in the fields of central Virginia called Trevilian Station. The largest all-cavalry battle of the war took place there on June 12, 1864.  It was a loss for the Union troops and was almost the loss of Hugh’s life when a bullet went through his head, entering in front of his right ear and exiting in front of his left ear.

It was a loss for the Union troops and was almost the loss of Hugh’s life when a bullet went through his head, entering in front of his right ear and exiting in front of his left ear.

Left for dead, a Confederate soldier was scavenging through his pockets later that day and found he was still alive. In a remarkable display of compassion, he took him to a barn and then to a hospital where he remained for three weeks, giving him a chance to reflect on the miracle that he experienced. But from there, Hugh went to a prison.

It costs money to keep prisoners of war, so a prisoner exchange program had been worked out between the two armies but it soon collapsed. Paroling the diseased and wounded was more common since they were simply deemed a liability. Hugh was imprisoned just three weeks before being sent to Richmond, then by boat to Annapolis for three more weeks, then being discharged home to Philadelphia in October.

Somehow the bullet didn’t harm his hearing or vision, but the effects of his near-mortal injury never left him. He returned to the shoemaking trade and married Rebecca Carson in 1866 at 11th Street Methodist Episcopal Church. Their first child lived only five days but they were able to raise Samuel and Mary to adulthood.

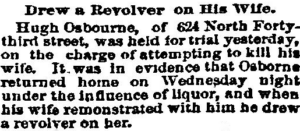

The 1880 census had the family living at 532 Pine Street in Society Hill where Rebecca was no mere housewife. She ran a boarding house at 531 Pine, with 20 boarders and three domestics. Three of the boarders were also shoemakers, but by 1885 Hugh left the leather work as his wife’s business eclipsed his. Perhaps he was still suffering the effects of his wounds, emotionally  and physically. Domestic trouble came to light when this newspaper story was printed in 1892.

and physically. Domestic trouble came to light when this newspaper story was printed in 1892.

Having grown up in a rooming house environment, son Samuel worked for his mother and together they owned and operated the Hotel Osborne in Atlantic City from 1893-1907, afterward owning the Hotel Arlington. Meanwhile, Hugh spent his last years chronicling the days he spent in the service, and died of a heart attack in 1895.

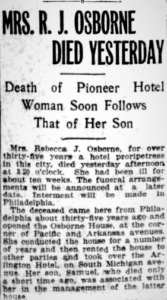

Both Samuel and Mary got married and moved to Atlantic City after their father died. Samuel and Rebecca became wealthy and well-known at the resort town where they lived until 1919; Samuel died on April 19, Rebecca on May 19. Mary had died eight  months earlier and

months earlier and  was buried with her father at Mount Moriah. After Rebecca was buried here, part of her fortune paid for this large monument placed next to the small marker to the left that was Hugh’s original stone. As for Samuel, his family chose to bury him in Atlantic City after splitting Rebecca’s estate with Mary’s family.

was buried with her father at Mount Moriah. After Rebecca was buried here, part of her fortune paid for this large monument placed next to the small marker to the left that was Hugh’s original stone. As for Samuel, his family chose to bury him in Atlantic City after splitting Rebecca’s estate with Mary’s family.

Support the Friends of Mount Moriah

Help us in our mission to restore and maintain the beautiful Mount Moriah Cemetery by donating to our cause or volunteering at one of our clean-up events.