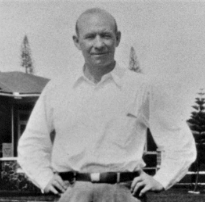

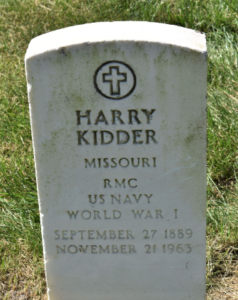

Title: Army Private, Navy Chief Radioman, cryptology instructor, World War I and II; bartender

Birthdate: September 27,1889

Death Date: November 21, 1963

Plot Location: Naval Section 4, Row 10, grave 20

When Harry was born in Farber, Missouri, the farming community had 272 people, which is more than it does today. He was an only child whose early life was undocumented and perhaps unremarkable except for his interest in telegraphy. The 1910 census places him in Fort Worth, Texas where he, like two other boarders in his rooming house, was a telegraph operator, launching his lifelong career in communications technology.

He put his skills to work for Uncle Sam when he joined the Army later that year. Harry’s time was spent in the Signal Corps as a telephone operator at Fort MacKenzie, Wyoming. He was discharged in October, 1913 and wasted no time in beginning a lengthy 21-year Naval career in January 1914.

It was here that Harry distinguished himself as Chief Radioman (CRM, or RMC for Radioman Chief Petty Officer on his gravestone), specializing in cryptology, intercepting and decoding messages of foreign navies. Between 1914 and 1925, he was stationed in the Asiatic Fleet, primarily at the Naval Radio Control Station at Los Banos, Philippines. Harry became one of the best radiomen in the fleet – traveling from his home base to ship after ship, assisting less experienced radiomen.

Quoting from his 2019 induction into the Hall of Honor at the National Security Agency, he was “one of the ablest radio operators in the US Asiatic Fleet in the early 1920s, [and] became interested in Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) transmissions. Chief Kidder taught himself Japanese syllabary and IJN radio procedure. The value of his IJN intercepts was recognized up the chain of command to Washington.”

In 1928 the Chief of Naval Operations authorized a school to train operators to monitor Japanese naval communications. The school became known as the “On the Roof Gang” because it met in a secretive “block house” on the roof of the old Navy Department building on the Mall in Washington D.C.

After designing and building the classroom and developing the radio intelligence curriculum, Harry instructed the first three classes of “Roofers” from 1928 through 1930. Since he was older and more experienced, he became known as “Pappy” to the group, and they respected him for the groundbreaking nature of his work.

The first “cryptologists” served in ground stations in the Pacific and later were on board ships, launching the Navy’s modern intelligence-gathering effort. The school taught nearly 200 operators in the years before World War II. Harry returned to the Pacific Fleet in 1931 to inspect and assist the new intercept sites, then returned to teach more classes.

After Harry’s official retirement in 1935 he bought a permanent residence in St. Petersburg where he took up bartending. He was active in amateur radio, became a baseball reporter for the local newspaper, and continued to drill annually with the Navy Reserves. His expertise was still needed, so he was recalled to active duty for most of 1941 and 1942 to help establish new intercept sites for the war effort. After the war he resumed his bartending job  and remained unmarried, but listed no occupation in the 1950 census in St. Petersburg.

and remained unmarried, but listed no occupation in the 1950 census in St. Petersburg.

Harry’s last years were spent at the Philadelphia Naval Home, and it was there he died of cancer in 1963. There was no one to telegraph the passing of his life and the role he played in protecting his country. Recognition of his pioneering work would only come years later from those in the National Security Agency, the U.S. Fleet Cyber Command and the cryptologic technicians of today’s Navy who are still learning from the work of Harry Kidder.

Support the Friends of Mount Moriah

Help us in our mission to restore and maintain the beautiful Mount Moriah Cemetery by donating to our cause or volunteering at one of our clean-up events.