Title: Army Private, World War I POW, Purple Heart recipient; accountant

Birthdate: January 17, 1902

Death Date: July 16, 1951

Plot Location: Section 53, Lot 46

George’s father had the same name as his son and worked as a streetcar conductor in Philadelphia, as did his father. George Sr. was 21 when he married Isabella Carmichael and lived in the Mill Creek neighborhood of West Philly where their daughter Helen was born in 1900 and George Jr. in 1902.

Some underlying but unknown trouble developed in 1908 that tore the marriage and family apart. George’s father turned suicidal and took his life by carbolic acid poisoning. Suddenly, Isabella was a single mom until she found and married Oscar Watkins in 1911. The family lived at 1243 North 57th Street, close to where Oscar worked as a carpenter for the Pennsylvania Railroad. George never used the “Jr.” suffix after that.

With the country’s entry into the Great War there were three draft registrations, the last occurring in September, 1918 when the age range was extended to 45 years old. Oscar was 41, so he complied. George had already enlisted on May 3, 1917 without registering. He wouldn’t have been able to, had he given his correct age, which was only 15.

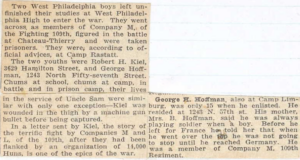

George had his mother’s permission but, as often happens, such a decision is made in conjunction with one’s peers. Private Hoffman went through basic training with his high school friend, Bob Kiel, and they were both assigned to Company M of the 109th Infantry. They didn’t leave for France until May 3, 1918, with their first engagement being the Second Battle of the Marne, July 15-18.

(Another soldier in Company M was 19-year-old John Black Rodgers of Philadelphia. He was wounded in a separate action, later receiving the Purple Heart, and was buried at Mount Moriah. Read his Notable life story here.)

It was the last major German offensive and the beginning of a series of Allied Victories that led to the war’s conclusion. It was also the last engagement for George and Bob; they were both wounded and captured as prisoners of war, taken first to be processed at Camp Limburg, then to an Internierungslager (“Internment Camp”) at Rastatt, just inside the German border. Both needed medical attention; George was hit by shrapnel to the neck and Bob was shot in the leg. These two local newspaper stories were printed sometime that fall.

They were initially listed by their captain as missing, but were fortunate that the POW camp was monitored by the International Red Cross, which sent a telegram from Switzerland to George’s mother on August 26 to report that he was alive and well. The Germans also permitted the American Red Cross to regularly distribute boxes with a 10-day supply of food for the Rastatt POWs, as shown here. An Allied naval blockade of Germany was causing famine conditions in the country, so the irony of plentiful POW food was not lost on the local population.

An Allied naval blockade of Germany was causing famine conditions in the country, so the irony of plentiful POW food was not lost on the local population.

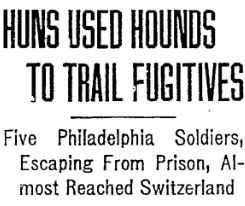

Sometime in either September or October, George was part of an  escape attempt, led by one of his fellow Philadelphians. Private Thomas Phillips wrote this to his father after the war was over: ” The five of us eluded our guard, got down the Rhine River for some distance, and when almost over the Swiss border the Germans, tracking us with hounds, recaptured us, and we were returned to a bread and water diet for our punishment.”

escape attempt, led by one of his fellow Philadelphians. Private Thomas Phillips wrote this to his father after the war was over: ” The five of us eluded our guard, got down the Rhine River for some distance, and when almost over the Swiss border the Germans, tracking us with hounds, recaptured us, and we were returned to a bread and water diet for our punishment.”

The November 11 Armistice meant the end of fighting but freedom wasn’t immediate. After five months of imprisonment, his record listed “repatriation” on December 16 and a return to duty on January 13, 1919. His relationship with the Army was officially over on May 25 of that year while he was still a teenager.

According to one census report, George finished his high school education and found his lifelong vocation as an accountant. He married an 18-year old named Winifred Yearsley in 1924 but the marriage was not destined to last. They had two children, Winifred in 1931 and George in 1935, while they were living in the suburb of Havertown, Delaware County. In 1940 they were separated and she had the children at the Media Inn in nearby Media. When he registered for the draft in 1942 he and his widowed mother were living with his sister’s family five miles away in Drexel Hill.

George died nine years later from acute bronchitis. He was back in the city at 6315 Woodland Avenue, just two blocks south of Mount Moriah. His death certificate says he was an accountant and divorced when he died at age 49, and it was signed by his sister Helen.

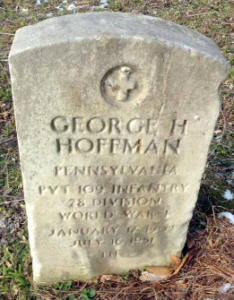

He was buried in his father’s plot, as was his mother just a year earlier. Helen submitted an application for a military headstone and when it was approved it was marked “Purple Heart” although no other supporting documentation has been located. The letters “PH” at the bottom of his headstone honor George’s sacrifice with this recognition.

Support the Friends of Mount Moriah

Help us in our mission to restore and maintain the beautiful Mount Moriah Cemetery by donating to our cause or volunteering at one of our clean-up events.