Title: Navy 2nd Assistant Engineer, Mexican War; State Department "detective"

Birthdate: October 20, 1826

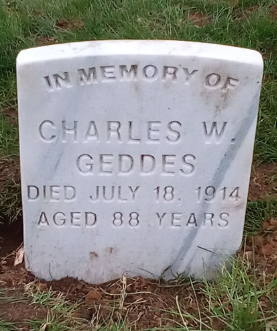

Death Date: July 18, 1914

Plot Location: Naval 3, Row 7, Grave 1

During the Civil War, the South had several major ports but no shipping industry, few dockyards to build ships, few machinists, and few facilities to produce iron. What the South did have was cotton which supplied England’s vast textile industry, and it was exchanged for the South’s never ending demand for ships, rifles, medicine, and other manufactures for war.

Steam ships were needed to break the Union Navy’s blockade of Southern ports, export the cotton, and bring back the tools of war. British-built, full-rigged, auxiliary steam powered ships were sought after by the Confederates for use as commerce raiders, a strategy designed to divert the Union Navy’s resources away from blockading Southern ports.

Consequently, the Union’s State Department, through their consular offices in Europe, employed a network of spies to ferret out information about Confederate activity, especially in England. The Confederate Navy operated from two cities, London and Liverpool. The Union divided their spy network accordingly: Liverpool was overseen by US Consul Thomas Haines Dudley, and London was directed by US Consul Freeman Harlow Morse.

The State Department’s spies watched England’s dockyards for ships under construction capable of serving the Confederate Navy and merchant ships transporting war supplies through the blockade. Warships needed crews, and Union spies also followed Confederate naval officers, engineers, and petty officers brought to England to await new assignments. The top targets for Union spies eventually became the Confederate commerce raiders, which were merchant ships built to evade England’s Foreign Enlistment Act, and then converted to cruisers beyond British territorial waters.

One of the top agents sent by the Confederate Navy to procure warships was Commander James Heyward North, of South Carolina. He had been a Lieutenant in the US Navy prior to the Civil War and was assigned to “Special Services Abroad.”

It was in Paris in July, 1864 when a baffled Commander North confided to a friend, “we have almost given up in despair ever being able to do anything in England. The federals have so many spies and they are so active that it is impossible to do anything no matter how secret we may act, or how few we have engaged in it.” What Commander North didn’t know was his confidant was one of the State Department’s top spies, or “detectives,” code named “G.”

In a report, Consul Morse commented about G, “He is considered by most, or all of them [the Confederates] who knew him, as one of their number and they speak as unreservedly to him about their doings as they do to each other.”

“G” is buried in Mount Moriah’s Naval Asylum Plot. Born in Baltimore on October 20, 1826, Charles Wright Geddes (AKA C. Wright Geddes and C.W. Geddes) came to Philadelphia as a young man to study engineering at the Franklin Institute. Upon completion of his studies, Geddes was appointed to the US Navy as 3rd Assistant Engineer aboard the USS General Taylor in November 1847 during the Mexican War. Geddes later served aboard one of the Navy’s first steam powered warships, the side wheeler USS Mississippi, during a cruise into the Mediterranean. However, his career with the Navy ended in August 1859 when he had to decline a promotion to First Assistant Engineer due to “malaria fever.”

At the start of the Civil War, Geddes “went South,” joined the Confederate Navy for a short period and served as First Assistant Engineer aboard the CSS Lady Davis at Savannah, GA. His father, Robert Geddes, gained a position with the Confederate Post Office in Richmond, but at the same time, his son Charles resigned from the Confederate Navy. In June of 1861, Charles married the niece of former US Senator Isaac Hayne of South Carolina and was living in Charleston. Geddes’ initial service in the Confederate Navy is confirmed by captured Confederate records.

Life started to unravel for Geddes in early 1862. His wife and child died in Charleston and he was turned down by the Confederate War Department for an appointment as First Lieutenant with their Army’s Engineer Corps. This is where his story gets murky.

During the summer of 1862, Geddes crossed through the Confederate lines and turned up in Nashville, Tennessee at the headquarters of Union General William S. Rosecrans, on his staff. According to his obituary, Geddes was appointed to assist Captain Nathaniel Michler, Rosecrans’ chief of Topographical Engineers. After previously resigning from the US Navy and before the war, Geddes had prior experience as a surveyor mapping out townships and borders in Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma.

General Rosecrans was known for being the most well prepared general in the Union Army. He relied heavily on his engineer staff for topographical maps. Merged with intelligence obtained from his scouts and “secret service,” overseen by his notorious Chief of Army Police, “Colonel” William Truesdail, Rosecrans’ staff provided his Army of the Cumberland with a clearer picture of the battlefield.

Geddes’ obituary says that in preparation for the Battle of Stones River (near Murfreesboro, Tennessee, December 31, 1862-January 2, 1863), Geddes was assigned to trail Confederate General John Hunt Morgan’s troops and report back to headquarters on their movements. Geddes was allegedly captured by Confederates. In his possession were papers from Morgan’s headquarters. He was soon awaiting trial as a spy. “By a ruse,” according to his obituary, Geddes escaped and again picked up where he left off, trailing Morgan’s forces.

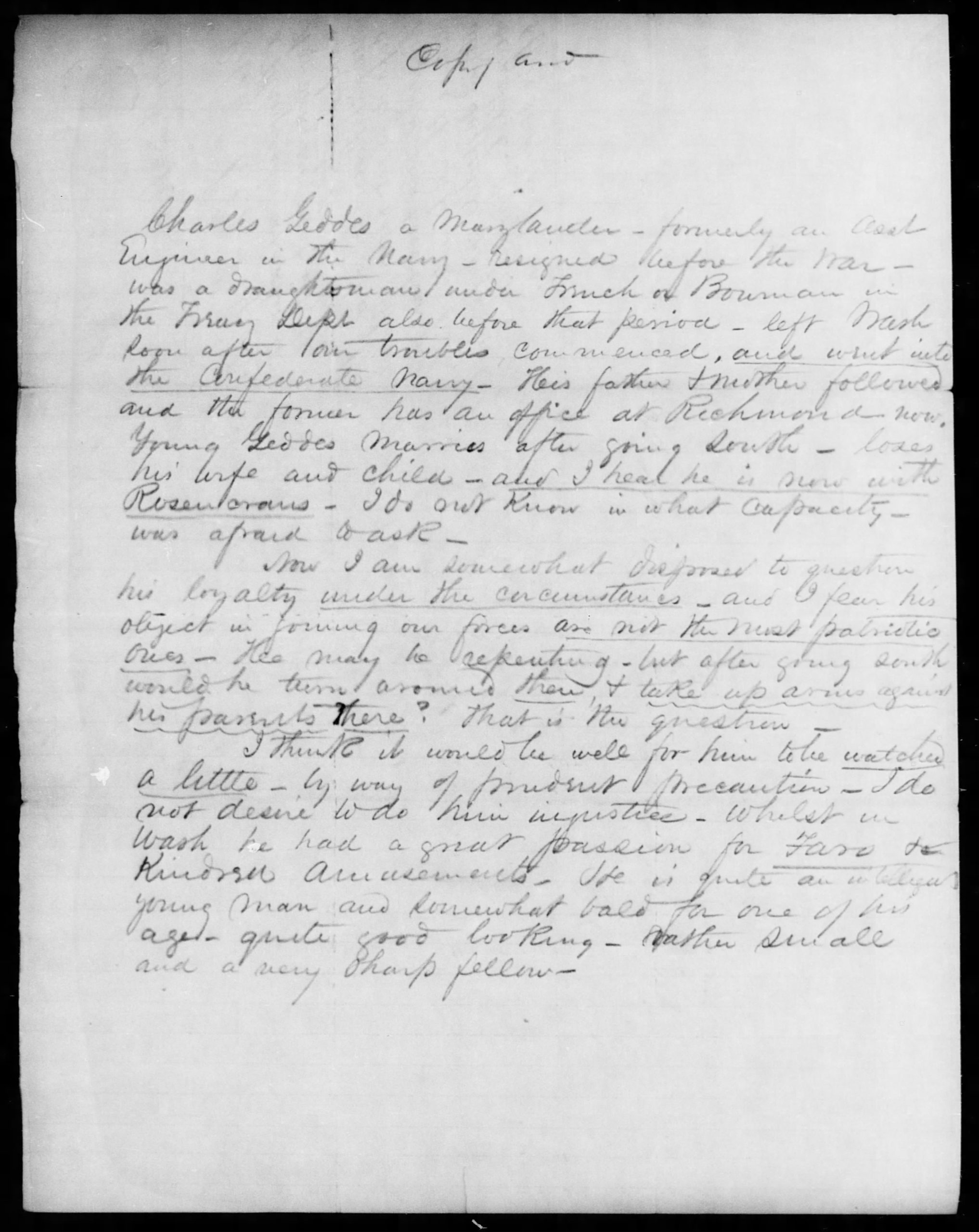

Meanwhile, in late March 1863, according a document found in the National Archives (see below), an unknown informant provided details of Geddes’ pre-war background, his penchant for gambling, his service in the Confederate Navy, and his sudden appearance on Rosecrans’ staff. Geddes seemed to be well connected in Washington, DC circles, but the informant suspected that Geddes may actually be a double agent. The informant considered Geddes to be a “sharp fellow” who needed to be watched. The matter was referred to Rosecrans’ spy chief, “Colonel” Truesdail, for further investigation.

After Geddes escaped from Morgan’s forces, he was again recaptured and imprisoned at Knoxville, Tennessee. When General Ambrose Burnside’s forces captured the Cumberland Gap and threatened Knoxville in September 1863, Geddes’ Confederate captors moved him to a military prison for officers in Columbia, South Carolina with orders to hold him until the end of the war.

Again, Geddes allegedly escaped from this Confederate prison and suddenly turned up in England “on a secret mission for the government.” While Union POW escapes from Southern jails were common, this capture-escape-recapture-escape scenario in his obituary has, so far, not been confirmed by historical records. Geddes’ lengthy obituary in the Army-Navy Register neglected to mention that he actually served in the Confederate Navy and instead mentioned only that he went to Charleston to marry his wife and seek an appointment as an engineer, but “this appointment was not accepted.” His New York Times obituary stopped with his naval service in the Mexican War.

In the public mind, spies were considered unsavory, deceitful figures. They only became martyrs for the cause, by one side or the other, after they had been captured and executed. The capture and escape scenario might have been a “rouse” the obituary writer used to get Geddes from Tennessee to London to make his story more sympathetic to readers. During this period General Rosecrans had been defeated at Chickamauga and sacked. Rosecrans may have simply recommended Geddes, with his naval background and prior service with the Confederate Navy, to Secretary of State William H. Seward for an overseas assignment.

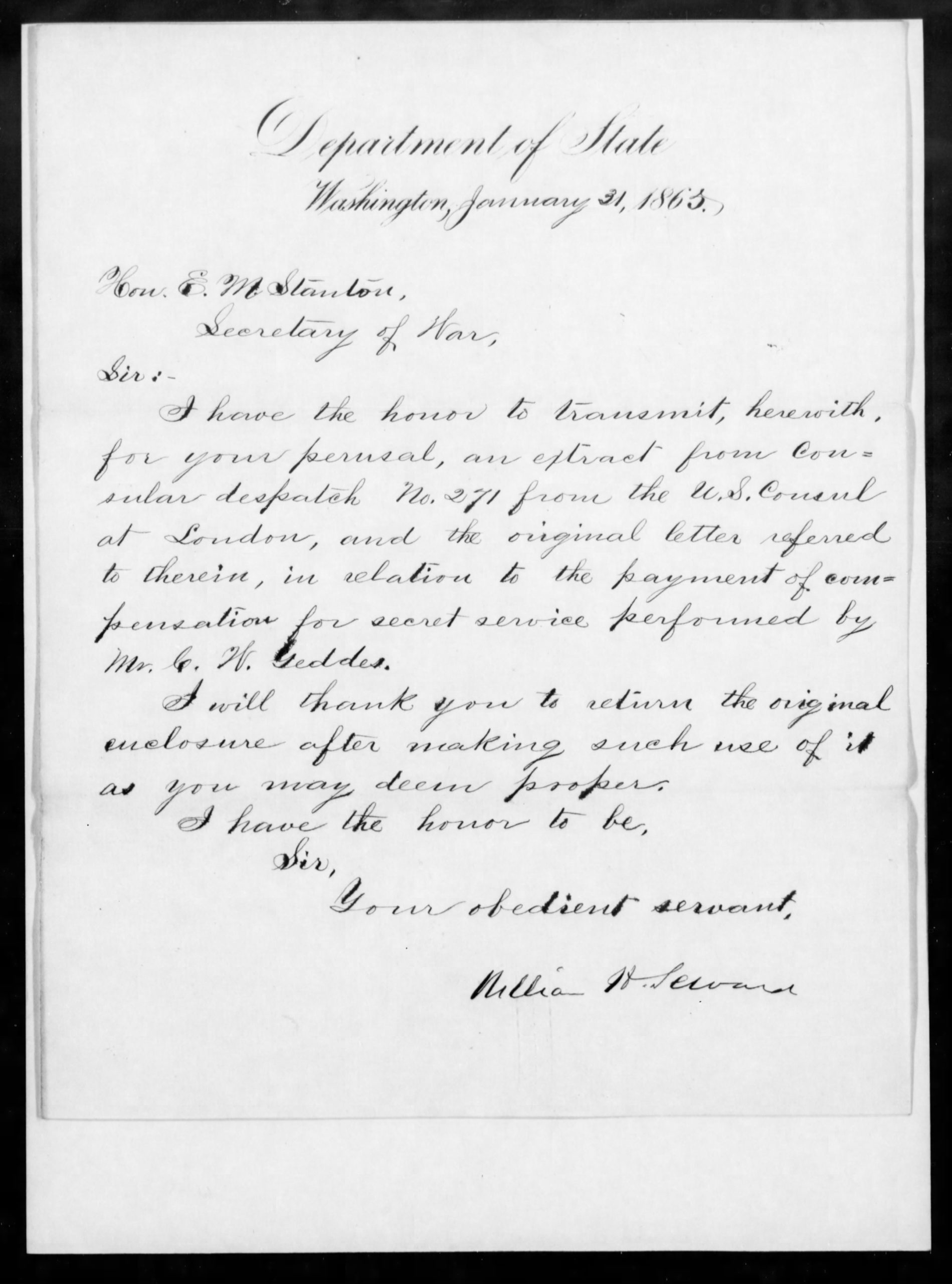

Geddes’ “secret mission” in London is documented in the National Archives. The letter below from Seward to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, dated January 31, 1865, requested compensation for “secret services performed by Mr. C. W. Geddes.” This confirms that Geddes was a spy for the Union in London. John D. Bennett’s The London Confederates, briefly recounts Geddes’ exploits in London and Paris. A more comprehensive historical account of the State Department’s efforts to frustrate the operations of the Confederate Navy in London can be found in two parts beginning with this link:

http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2001/fall/confederate-fleet-1.html

Charles Wright Geddes, a Naval Home beneficiary, died at the U.S. Naval Hospital in Philadelphia on July 18, 1914, at the age of 87. According to his obituary, despite his incredible story, Geddes’ “only reward for his long service” to the country was “a pension of twenty dollars a month as a veteran of the war with Mexico” and a grave at Mount Moriah’s Naval Asylum Plot.

Support the Friends of Mount Moriah

Help us in our mission to restore and maintain the beautiful Mount Moriah Cemetery by donating to our cause or volunteering at one of our clean-up events.